Internet: Weblogs, YouTube und Cinephilie

The Video Essay

The video essay is often described as a form of new media, but the basic principles are as old as rhetoric: the author makes an assertion, then presents evidence to back up his claim. Of course it was always possible for film critics to do this in print, and they’ve been doing it for over 100 years, following more or less the same template that one would use while writing about any art form: state your thesis or opinion, then back it with examples. In college, I was assured that in its heart, all written criticism was essentially the same – that in terms of rhetorical construction, book reviews, music reviews, dance reviews and film reviews were cut from the same cloth, but tailored to suit the specific properties of the medium being described, with greater emphasis given to form or content depending on the author’s goals and the reader’s presumed interest.

There was always a caveat, though – one that didn’t become clear until about seven or eight years ago, when sophisticated, affordable editing software and DVD-ripping programs became readily available to consumers. Simply put, written reviews of print media always had a huge advantage over all other reviews in terms of their ability to quote bits and pieces of the thing being written about. Only when evaluating written work could a reviewer precisely reproduce the texture, the essence, the reality of the thing being critiqued, and nestle that piece of the work within the context of his own arguments and sensibility.

|

[Matt Zoller Seitz: A Little Love: The Art of Bill Melendez (US 2008)]

A critic reviewing Ernest Hemingway’s »The Sun Also Rises« could, for example, assert that the author’s style favors direct, stripped down sentences largely bereft of adjectives, then present the following snippet by way of illustration: »It was like certain dinners I remember from the war. There was much wine, an ignored tension, and a feeling of things coming that you could not prevent happening. Under the wine I lost the disgusted feeling and was happy. It seemed they were all such nice people.« That passage is not an approximation of what Hemingway wrote; it IS what Hemingway wrote – minus, of course, its larger context.

|

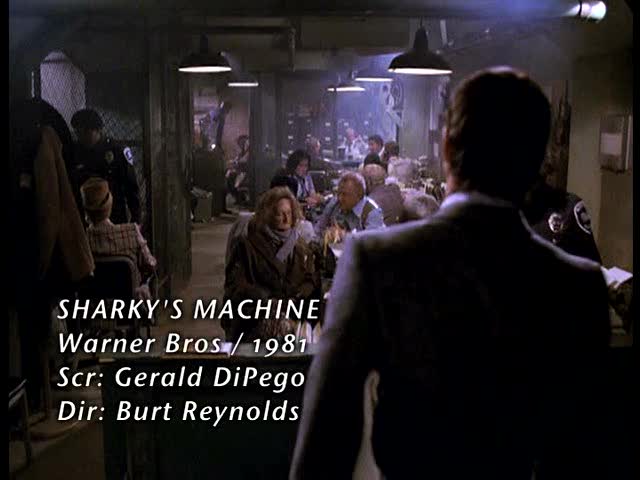

[Matt Zoller Seitz: Review: »Sharky's Machine« (US 2008)]

In contrast, a film reviewer trying to describe the style of Martin Scorsese would have to rely on approximations: descriptions of Scorsese’s dancelike camera moves, for example, or his voluptuous deployment of pop music, or his disruptive use of sound effects. Depending on the author and the requirements of his publication, such descriptions could be truncated or obsessively detailed, factually accurate or wildly off-base; they could concentrate on form, content or some combination; they could concern themselves with the filmmaker’s style or with his choice of subject matter and thematic preoccupations. But the one thing they couldn’t do was quote – really quote – the object of criticism, the better to examine, illuminate or vilify it. There were always exceptions here and there, naturally. The film history texts of David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson and other like-minded writers illustrated their assertions about shot composition and editing patterns with stills from the films being discussed – a major advance over texts that relied on studio-produced publicity photos that often bore little or no relation to what the spectator actually saw while watching the films in question. And there have always been documentary films about cinema history and style that used film clips to advance their arguments. Notable examples include the narrated, stand-alone pieces on particular movies, directors and actors that used to appear on Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert’s syndicated movie review programs Sneak Previews and At the Movies; A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies; Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinema; Mark Rappaport’s Rock Hudson’s Home Movies and From the Journals of Jean Seberg, and Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself.

|

|

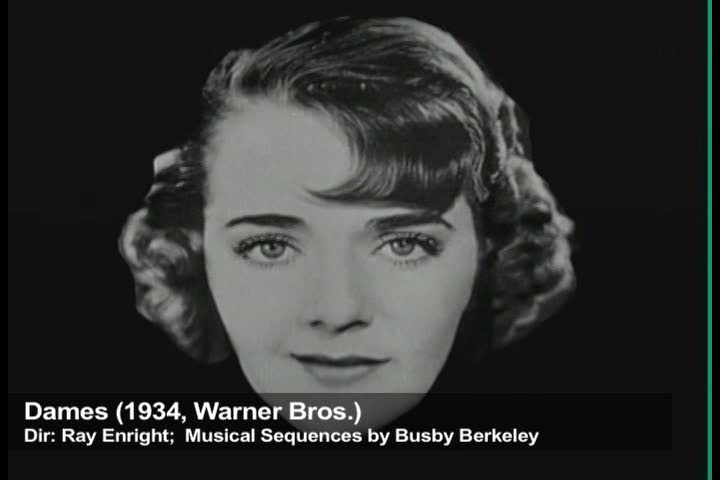

[Matt Zoller Seitz: Berkeley(esque) (US 2008)]

But such heroic efforts were always complicated by two factors: the time, expense and complex production process once required create such works, and the necessity of seeking approval of copyright owners before quoting anything.

The first problem has been effectively obliterated thanks to technological advances. The combination of digital editing software and DVD ripping programs – I use a combination of Handbrake, Mac the Ripper and MPEG Streamclip for my own pieces – allows a critic to deconstruct a movie and recontextualize it with a degree of freedom comparable to that of a literary critic. The end result can be as drily analytical or as freewheeling as the filmmaker wishes – as expressive of individual sensibility as the work being examined.

The second problem is more vexing, thanks to media companies’ attempts to ignore, subvert and otherwise neutralize fair use provisions of copyright law – an exemption that permits selective quotation for purposes of criticism, commentary, education and parody. It’s strictly a bottom-line issue: companies wish to prevent anyone from quoting any part of a film or television program for any reason without official permission plus a fee, because looking the other way would (in their minds) condone a minor form of the piracy that saps so much revenue from their coffers.

Book, magazine and newspaper publishers have rarely gone to such lengths to control the quotation of written work. This is partly because anyone with eyes and a writing instrument could copy a written passage, and partly because written expression has always been intertwined with a common-sense approach to copyright law, with an awareness that culture is a living, breathing entity that must feed on itself in order to grow.

Now that the process isn’t hard anymore, copyright holders are adopting a zero-tolerance policy – embedding digital watermarks in their content, scouring the internet for any reproductions of that content, no matter how brief or recontextualized, and sending notices to video upload services (such as YouTube) demanding the removal of any videos containing that content. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DCMA) requires that service providers remove any content that the copyright holder deems infringing; the person who used that content can protest the takedown, and if the copyright holder doesn’t take further action after two weeks, the content has to be restored. The DCMA also warns that copyright holders who knowingly file or are a party to frivolous takedown notices can face legal and financial penalties – the flipside of holding copyright violators legally accountable for their actions.

This seems like a reasonable way of regulating a vast and perhaps unpoliceable new frontier – after all, with millions of new video uploads occurring each day, copyright holders (and video upload services) simply don’t have enough time or manpower to sift through all the videos individually and decide which are truly violating copyright and which are utilizing copyrighted material in a way that’s protected by the notion of Fair Use. Unfortunately, both the digital-watermark scanning software and the email programs that automatically send notice-and-takedown messages to service providers don’t distinguish between somebody who’s uploading the entirety of Battlestar Galactica (not protected speech) and someone who uses a minute and fifteen seconds of the series in a larger piece about the portrayal of women in science fiction (absolutely protected). As for the ideal of penalizing copyright holders who file frivolous takedown notices, there have been a few examples of this happening; but the system is still stacked against the video essayists, most of whom are independent artists who don’t have the time, money or knowhow to mount a legal attack against those who are interfering with their legally protected right to use Fair Use-exempted material online. And due to widespread ignorance of the law, people who use copyrighted material in online videos tend to recoil in fear at the first sign of a takedown notice, not realizing that they have some recourse, however limited.

|

|

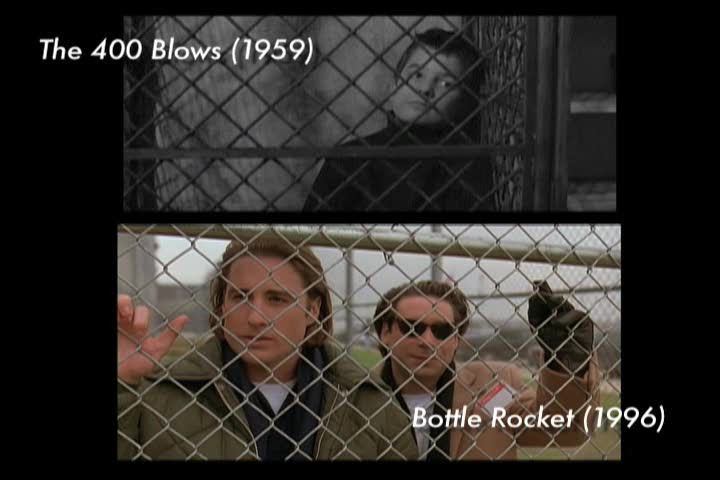

[Matt Zoller Seitz: Wes Anderson: The Substance of Style – Part 1 (US 2009)]

However, technology’s forward march being what it is, one suspects that these problems will resolve themselves in due time. It seems inconceivable that takedown notice-abusers could eventually win out in this struggle; with so much of the world getting used to near-total freedom of expression online, the idea that one would have to seek someone’s permission before criticizing or commenting upon their work is not just anathema to reason, it’s faintly fascistic, and as such, cannot be sustained. On top of that, what we’re seeing on YouTube and other sites is the New Normal – the new way of thinking, communicating, interacting with the world. A new generation of critics and artists are comfortable with a collage-type approach to expression, one that appropriates bits and pieces of media and puts them in a new framework -- everything from so-called »mash-up« videos to humor pieces that utilize television news footage to more theoretical works like the ones created by such video essayists as Kevin Lee. And with each passing year, indeed each passing month, the means of expression becomes more supple, the language more expressive. It is already possible for video essayist to express themselves with the same fluidity and idiosyncratic energy that they might bring to written text; just as a dedicated cinephile can identify a particular paragraph as the work of Pauline Kael, Manny Farber or André Bazin, it is also possible (already!) to see a snippet of one of Kevin B. Lee’s videos from the other side of the room with the sound off and say, »That’s got to be Kevin.« Bottom line: despite the best efforts of copyright holders and media companies to fence off this new frontier, it remains not only open, but also ever-expansive. The frontier is wide open.